Cross-section Microscopy Analysis of Interior Paints: Thomas Everard House (Block 29, Building 10), Williamsburg, Virginia Cross-section Microscopy Analysis Report: Thomas Everard House — Interior (Block 29, Building 10, Lots 165 & 166)

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1753

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

2013

CROSS-SECTION MICROSCOPY ANALYSIS REPORT

THOMAS EVERARD HOUSE — INTERIOR

Block 29, Building 10, Lots 165 & 166

COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG FOUNDATION

WILLIAMSBURG, VIRGINIA

This analysis was made possible by a generous grant from the Ohrstrom Foundation

and the Richard C. von Hess Foundation

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| Purpose | 5 |

| History | 5 |

| Previous Finishes Research | 6 |

| Comparison of Previous (1991) Findings to Present (2012) Results | 7 |

| Procedures | 7 |

| Summary of Results | 8 |

| Table 1. Thomas Everard House: Early Interior Decorative History | 11 |

| Stair Passage | |

| Description/History | 12 |

| Summary of Welsh (1991) Findings | 12 |

| Summary of Present (2012) Findings | 13 |

| Table 2. Stair Passage Decorative History | 15 |

| Sample Location Images | 17 |

| Staircase | 24 |

| Wainscot | 36 |

| Door Header | 37 |

| First—Floor Door Leafs and Architraves | 38 |

| Cellar Door Leaf and Trim | 43 |

| Upper—Floor Door Leafs and Architraves | 47 |

| First—Floor Lobby Woodwork | 50 |

| First—Floor Northwest Parlor | |

| Description/History | 52 |

| Summary of Welsh (1991) Findings | 52 |

| Summary of Present (2012) Findings | 53 |

| Table 3. Parlor Decorative History | 54 |

| Door Leafs and Architraves | 55 |

| Chair Rails | 61 |

| Wainscot and Paneling | 68 |

| Window Sash and Architraves | 76 |

| Cornice | 78 |

| First—Floor Dining Room | |

| Description/History | 80 |

| Summary of Welsh (1991) Findings | 80 |

| Summary of Present (2012) Findings | 81 |

| Table 4. Dining Room Decorative History | 82 |

| Door Architrave and Leaf to Study | 83 |

| Door Architrave and Leaf to Passage | 86 |

| Window Architraves | 89 |

| Wainscot | 91 |

| Cornice | 96 |

| Chair rails | 98 |

| 3 | |

| First—Floor Southeast Chamber (Study) | |

| Description/History | 100 |

| Summary of Welsh (1991) Findings | 100 |

| Summary of Present (2012) Findings | 100 |

| Table 5. Study Decorative History | 101 |

| Door Leaf to Dining Room | 103 |

| Overdoor | 104 |

| Stile | 105 |

| First—floor Northeast (Rear) Chamber | |

| Description/History | 106 |

| Summary of Welsh (1991) Findings | 106 |

| Summary of Present (2012) Findings | 106 |

| Table 6. Rear Chamber Decorative History | 107 |

| Door Leaf to Parlor | 109 |

| Door Architrave to Parlor | 110 |

| Upper Floor, Southwest Chamber | |

| Description/History | 111 |

| Summary of Welsh (1991) Findings | 111 |

| Summary of Present (2012) Findings | 111 |

| Table 7. Upper Floor, SW Chamber Decorative History | 112 |

| Closet Door | 114 |

| Window box | 117 |

| Passage door | 118 |

| Baseboard | 119 |

| Upper Floor, Northwest Chamber | |

| Description/History | 120 |

| Summary of Welsh (1991) Findings | 120 |

| Summary of Present (2012) Findings | 120 |

| Table 8. Upper Floor, NW Chamber Decorative History | 121 |

| Window box | 124 |

| Closet door | 125 |

| Door to small passage | 126 |

| Baseboard | 129 |

| Upper Floor, Small Passage between NW and NE Chambers | |

| Description/History | 130 |

| Summary of Welsh (1991) Findings | 130 |

| Summary of Present (2012) Findings | 130 |

| Door to NW Chamber | 132 |

| Door to NE Chamber | 133 |

| Upper Floor, Northeast Chamber | |

| Description/History | 134 |

| Summary of Welsh (1991) Findings | 134 |

| Summary of Present (2012) Findings | 134 |

| Table 9. Upper Floor, NE Chamber Decorative History | 135 |

| Door Leaf to Small Passage | 136 |

| 4 | |

| Polarized Light Microscopy Results | |

| Table 10. Summary of PLM results | 137 |

| Fluorochrome Staining Results | |

| Table 11. Summary of stain results | 150 |

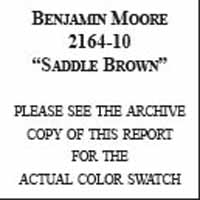

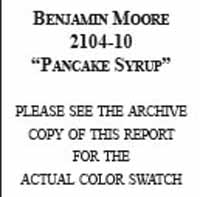

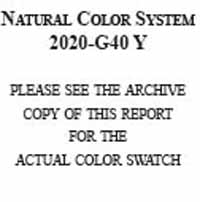

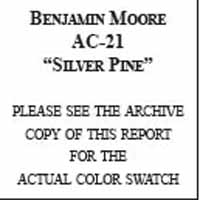

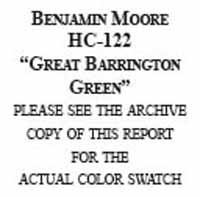

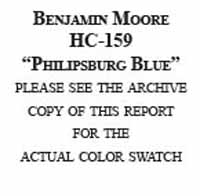

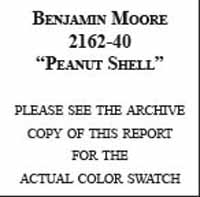

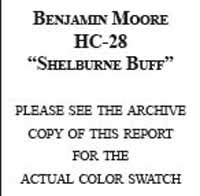

| Color Matching Results | 167 |

| Conclusions | 180 |

| References | |

| Appendix A. Paint Sample List | 183 |

| Appendix B. Procedures | 189 |

| Appendix C. Sample Memo 1 | 192 |

| Appendix D. Sample Memo 2 | 195 |

| Appendix E. Sample Memo 3 | 197 |

| Appendix F. Sample Memo 4 | 198 |

| Appendix G. Sample Memo 5 | 200 |

| Appendix H. Sample Memo 6 | 202 |

| Appendix I. Memo from E. Chappell | 203 |

Thomas Everard Interior Paint Study

Everard House, block 29, building 10

Everard House, block 29, building 10

Structure: Thomas Everard House, block 29, building 10, lots 165 and 166

Requested by: Edward Chappell

Roberts Director of Architectural and Archaeological Research

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Analyzed by: Kirsten Travers

Architectural Paint Analyst, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Consulted: Susan L. Buck, PhD.

Conservator and Paint Analyst

Williamsburg, Virginia

Date submitted: May 25, 2012

Purpose:

The purpose of this investigation was to use cross-section microscopy techniques to identify the early finish history of original interior woodwork in the Thomas Everard House. It was also hoped that the comparative paint stratigraphies would shed light on how the interiors evolved over time.

History:

The Thomas Everard House is a single story frame building with a prominent location on the Palace Green adjacent to the Governor's Palace. The house was built for John Brush, the town armourer and keeper of arms in the magazine and Governor's Palace. Dendrochronology indicates the main block, comprising the present stair passage and northwest and southwest rooms, was built in 1718, the refined staircase in the first-floor passage dates to 1719, and the northeast wing was added in 1720. During this period, the stair passage was expensively finished with fine woodwork including an ornate staircase with decorative brackets, raised panel wainscot, and crosseted door architraves. This woodwork is still in place. The first-floor rooms were more simply finished with baseboards and trim around the windows and doors. The walls were plastered and whitewashed. Brush occupied the house until his death in 1726.

From 1728-1742 the house was occupied by Elizabeth Russell and Henry Cary. Renovations to the interior made during this time could include the addition of chair rails in the first-floor rooms and a cornice in the parlor, but it is uncertain if these improvements were made during the Rusell/Cary period, or later (Klee, 18). It was hoped that the paint evidence would elucidate this question.

In 1742 the house was sold to William Dering, an artist and dancing master, who lived in the house until 1744. Documentary evidence suggests that Dering was deeply in debt throughout his brief occupancy, and none of the structural changes to the building have been ascribed to him (Klee, 20).

6It is unclear exactly when Thomas Everard purchased the property, but documentary evidence suggests that he may have moved into the house in 1756, after selling his house on Nicholson street to Anthony Hay. Born in London in 1719, Everard was orphaned by age 10 but emigrated to the colonies in 1735, when he was apprenticed to Matthew Kemp, a clerk with the General Court. Thomas Everard eventually became a wealthy landowner as well as a vestryman for Bruton Parish Church, a trustee of the public hospital, and mayor of Williamsburg. He would have moved into the house with his wife Diana and their two daughters (Klee, 20)

Two campaigns of improvement/renovation are attributed to Everard. The first (designated 'Everard Period I'), took place in 1756, when he is believed to have repainted all interior and exterior woodwork. The buffet in the first-floor southwest (dining) room may have been installed at this time. (Klee, 20-21).

In the next phase, c.1769-1773 (designated 'Everard Period II'), documentary evidence indicates that Everard carried out extensive renovations including construction of the southeast wing (study), and improvements to the first-floor rooms including the installation of cornices, new mantels, and paneled wainscot in the parlor and dining room, with new moldings applied to the door and window architraves. Similar woodwork was added in the east first-floor rooms (Klee, 21).

The house is currently interpreted to reflect the period of Everard's later occupancy, c.1773.

Following Everard's death in 1781, the house passed to Dr. Isaac Hall, who owned it until 1788. Following Hall, the house was owned by James Carter, who is believed to have demolished the southeast wing and installed a tight winder stair in the northeast wing to the upper floor (this addition must post-date the Hall occupancy, as is assembled with cut nails. Klee, personal comment, May 24, 2012). Carter occupied the house until 1819, after which it passed through a sequence of owners including the Smith family from 1849-1928, when it was purchased by the Williamsburg Restoration. The house was restored by Colonial Williamsburg in 1949. During this time the southeast wing was reconstructed, and any surviving wall plaster was removed and replaced.

Restoration-era paint specifications:

The following colors were specified for interior woodwork at the Brush—Everard House during the 1949 restoration (Kocher and Dearstyne 1952, 84-86). These colors were based on paint scrapes carried out at that time:

| Location | Color | Description | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| First floor, Stair hall | #437 | dark brown | all woodwork |

| Second floor, passage | #881 | gray | doors and woodwork |

Previous finishes research:

The interior woodwork was investigated by paint analyst Frank Welsh in 1991. Welsh's methodology entailed microscopic analysis of collected paint chips with low-power magnification and reflected visible light to record and compare the paint stratigraphies. Color matching was carried out by eye to the Munsell system of color notation. Cross-section microscopy and/or polarized light microscopy for pigment identification does not appear to have been carried out.

7Welsh determined that in the first generation (Brush 1719), all of the woodwork was painted with a medium red-brown (iron oxide), oil-based paint (Welsh 1991, 12). This color was found throughout the entire house. Welsh saw a thick layer of dirt on the surface of this red-brown paint which suggested that it had been exposed for approximately 15-20 years.

In the second generation (speculated to be Everard Period I, c.1756), every space was painted a different color. Welsh postulated that the northeast bedroom and stair passage woodwork was painted a light gray color. The woodwork in the first-floor southwest dining room was painted dark brown, and the parlor was painted a bright green color made with verdigris. The woodwork in the upper floor rooms was painted white and light gray (Welsh, 7).

The paint evidence confirmed that much of the woodwork, in particular the paneling, in the first-floor rooms was a later addition, speculated to reflect Everard Period II, c. 1770. At this time the parlor was painted a deep green color made with verdigris, while the dining room was painted a yellowish-white, and the northeast (rear) chamber was painted a pale yellow ochre. The stair passage was painted a medium brown.

Comparison of Welsh's findings with the present study:

In the twenty years since Welsh's paint study, significant advances have been made in the field of architectural paint analysis. The present paint investigation was carried out using the most up-to-date equipment and techniques including a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope with digital image capture for cross-section microscopy at high magnifications (40-400x) with both reflected visible and ultraviolet light as well as various filters for in-situ media characterization with fluorochrome stains. The same microscope was also used for pigment identification via polarized light microscopy with an oil-immersion objective for examination of particles at 1000x magnification. Color measurements were obtained from with a colorimeter/microscope with values given in both the CIE L*a*b* and Munsell color systems (see Appendix X). Welsh's samples were not available for re-examination and comparison, which would have been very helpful to the present study. For the present investigation, a newer and more extensive sample set was taken in collaboration with CWF architectural historians who have learned more about the house since 1991. As a result, the present investigation yielded new evidence and resulted in a fresh interpretation of the decorative history of the Everard house.

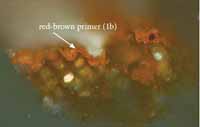

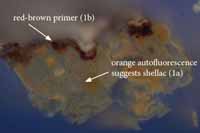

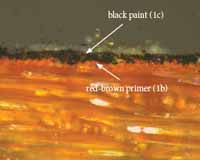

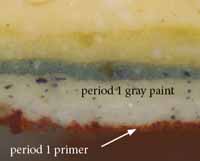

One of the most significant findings of the present paint study was that the first generation red-brown identified by Welsh in the stair passage and other rooms appears to have been a primer, not a finish coat. This paint layer was examined repeatedly at high magnifications and there was no dirt layer observed. In fact, the amorphous surface of this layer suggests it had not completely dried before the next paint was applied. Thus, the red-brown paint was interpreted as a primer, not a finish coat. Therefore, all of the following generations were applied earlier than previously thought. One consequence of this newer interpretation is that the house might have been painted in a polychrome scheme (each room a different color), shortly after the Brush occupancy, which is much earlier than previously thought.

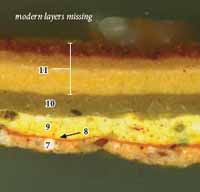

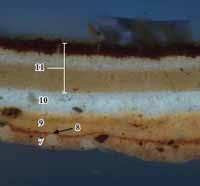

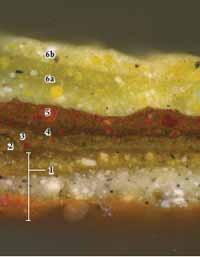

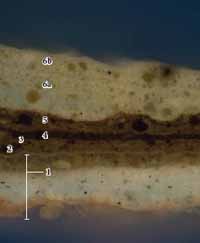

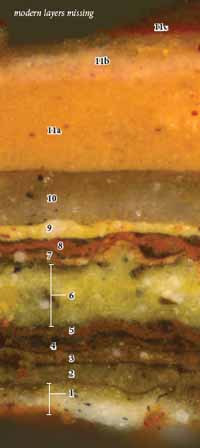

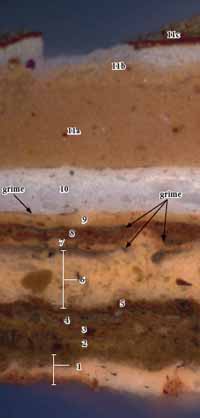

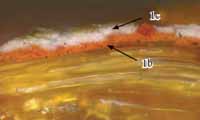

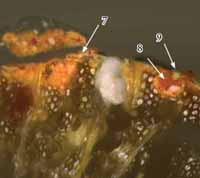

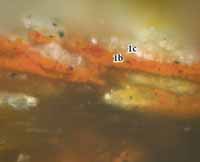

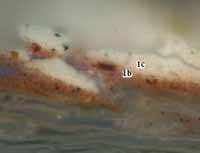

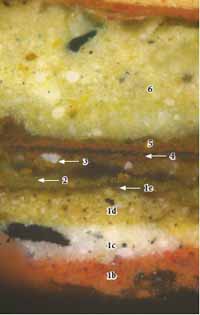

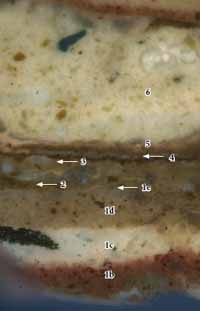

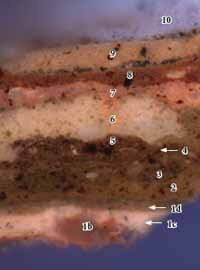

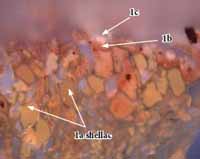

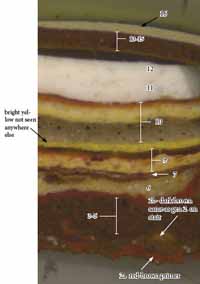

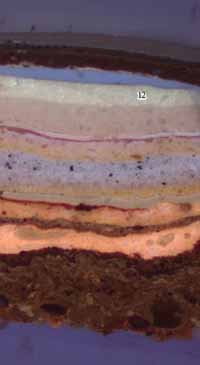

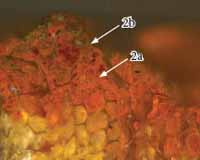

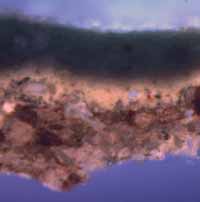

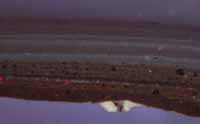

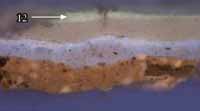

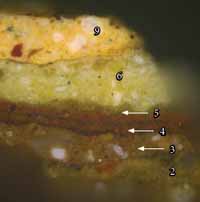

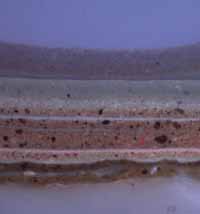

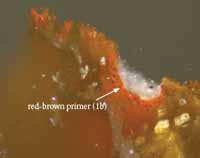

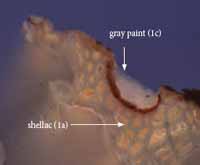

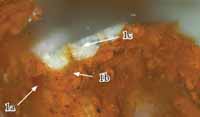

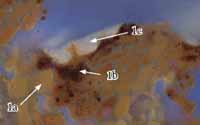

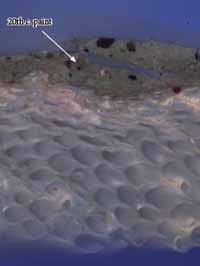

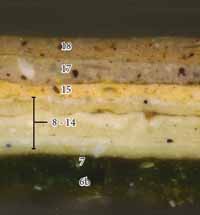

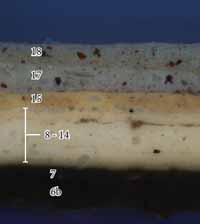

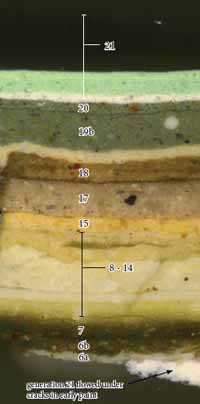

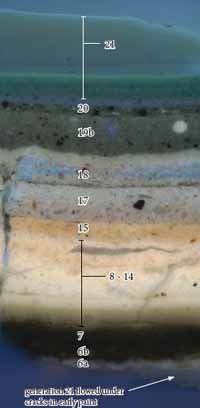

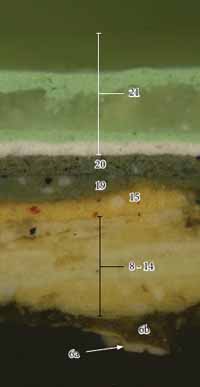

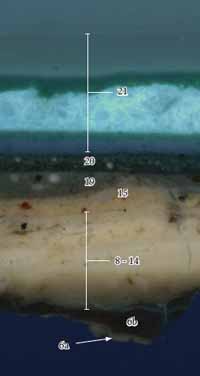

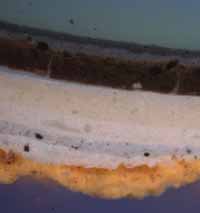

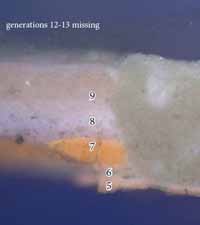

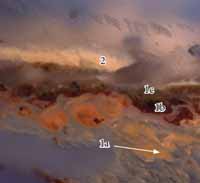

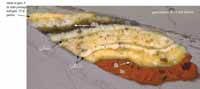

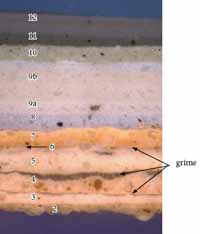

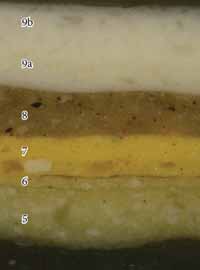

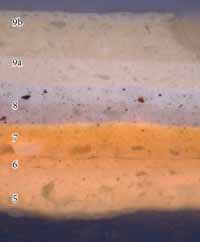

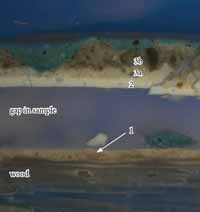

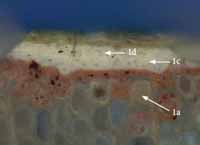

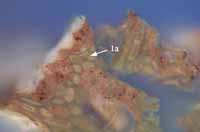

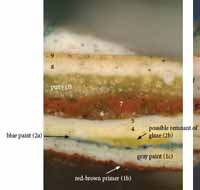

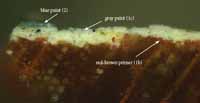

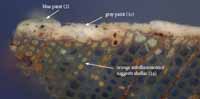

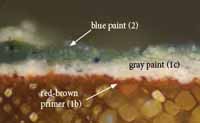

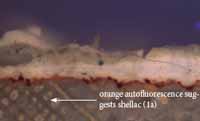

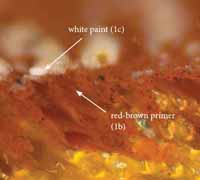

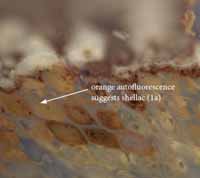

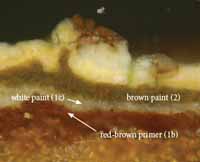

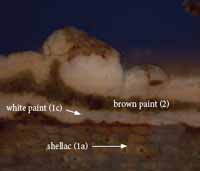

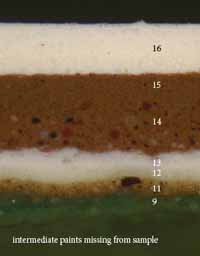

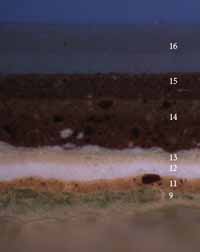

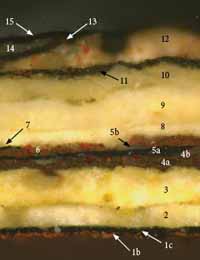

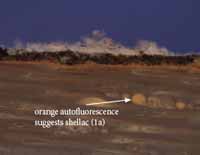

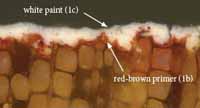

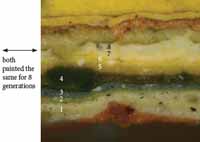

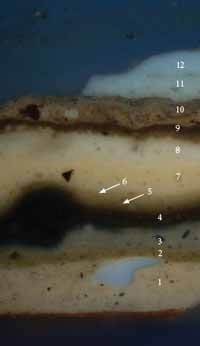

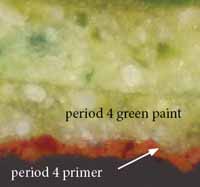

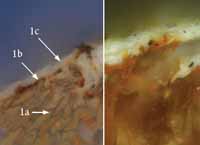

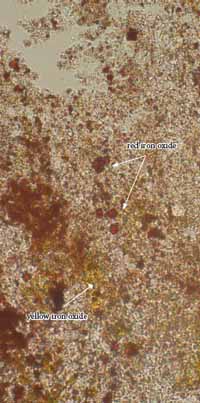

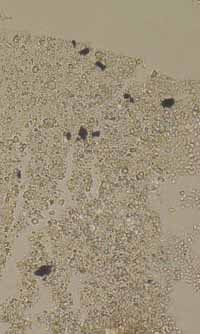

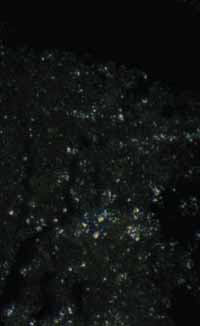

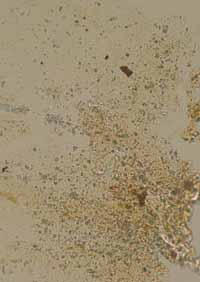

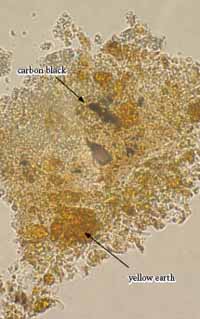

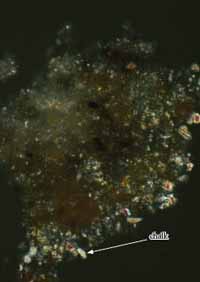

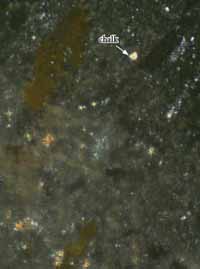

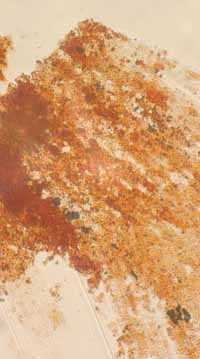

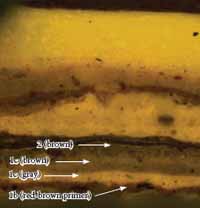

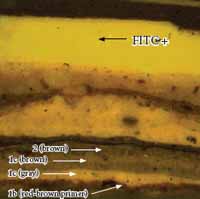

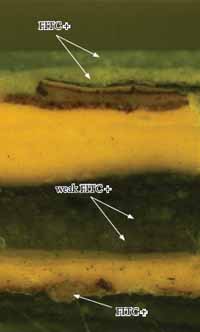

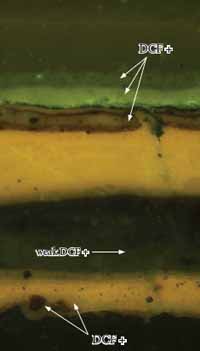

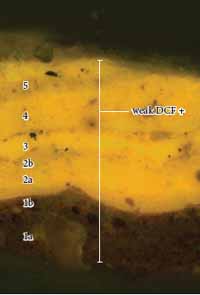

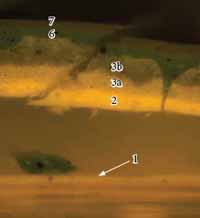

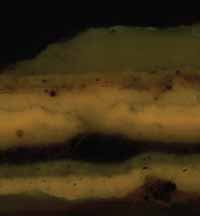

Another important discovery is that different red-brown primers appear to have been used throughout the house. The first period primer in the stair passage was more pinkish in color, while the red-brown primer used in the upper-floor rooms was much thinner and darker orange-red in color (see illustrations below for comparison). However, both of these primers were followed by the same first period coarsely-ground gray paint, suggesting that they are contemporary. In generation 4, another red-brown primer was used 8 in the parlor, which is also a deep orange-red color. However, this primer aligns with generation 4 in that space, much later than the previous two primers. All of these primers appear to have been made with red earth pigments.

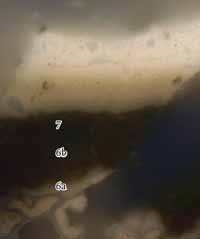

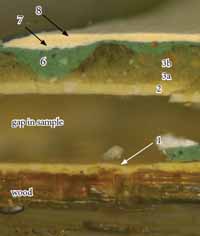

red-brown primer in stair passage, first-floor- door architrave to dining room (sample EV 27, 200x)

red-brown primer in stair passage, first-floor- door architrave to dining room (sample EV 27, 200x)

red-brown primer in upper-floor south-west chamber, closet door leaf (sample EV 101, 200x)

red-brown primer in upper-floor south-west chamber, closet door leaf (sample EV 101, 200x)

red-brown primer in parlor, door leaf to passage (sample EV 63, 200x)

red-brown primer in parlor, door leaf to passage (sample EV 63, 200x)

Procedures:

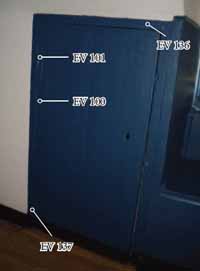

One hundred and thirty nine samples were collected from the house by Kirsten Travers who was usually accompanied on-site by CWF architectural historians Edward Chappell and Jeff Klee. On site, a monocular 30x microscope was used to examine the painted surfaces and determine the most appropriate areas for sampling. A microscalpel was used to remove the samples, which were labeled and stored in small individual Ziploc bags for transport back to the laboratory. All samples were given the prefix "EV" and numbered according to the order in which they were collected. All sample locations were documented and recorded. In the laboratory, the samples were examined with a stereomicroscope under low power magnification (5x to 50x), to identify those that contained the most intact paint evidence and would therefore be the best candidates for cross-section microscopy. Uncast sample portions were retained for future examination and analysis. The best candidates were cast in resin cubes and sanded and polished to expose the cross-section surface for microscopic examination.

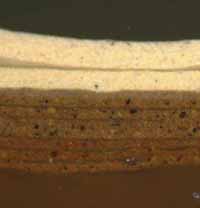

Once cast, the cross-section samples were examined and digitally photographed in reflected visible and ultraviolet light conditions at 20x to 400x magnifications. By comparing the resulting photomicrographs, finish generations could be interpreted based on physical characteristics such as color, texture, thickness, presence of dirt layers and extent of surface deterioration. Fluorochrome staining was also carried out on selected samples to characterize the types of binding media present (oils, carbohydrates, proteins). Polarized light microscopy was carried out on selected early paints to determine the pigment composition. Colorimetry was carried out to obtain color matches for early paints. The most informative photomicrographs and their corresponding annotations, as well as comments from the author, are contained in the body of this report. All raw photomicrographs can be found in the Appendix.

Results:

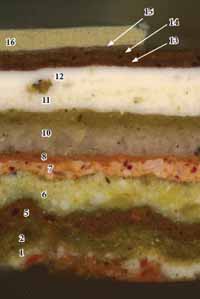

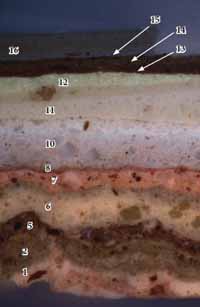

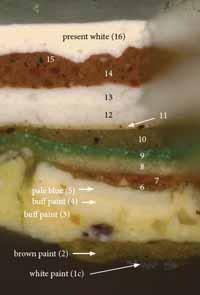

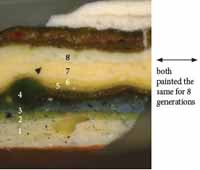

Most of the Everard woodwork contains intact, early finish evidence from which the history of the interior can be understood. Some findings were very straightforward, while others were much more complex. 9 The comparative paint evidence suggests the rooms were painted differently at different points in time, so precise generations are difficult to align. For instance, sixteen paint generations were identified in the stair passage, twenty—one in the first-floor northwest parlor, and twelve in the southwest dining room. This is an important finding that suggests the parlor was always maintained as a high status space, but this condition did complicate the overall interpretation.

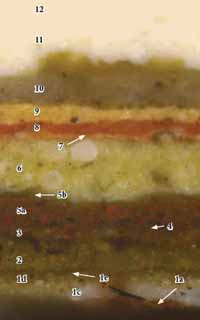

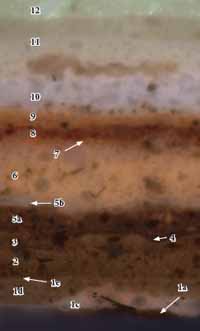

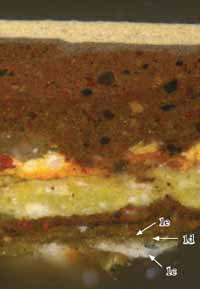

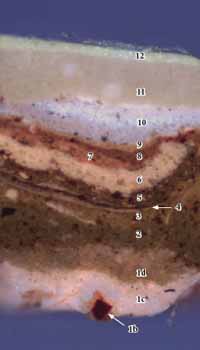

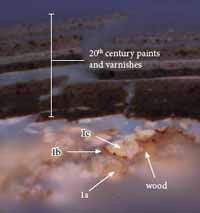

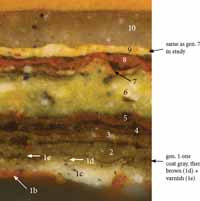

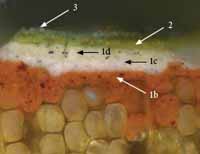

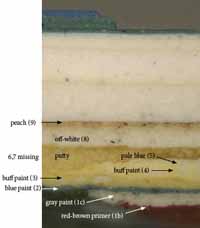

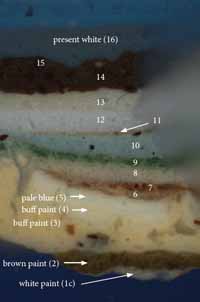

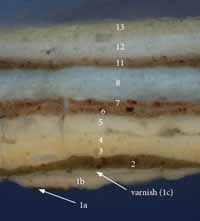

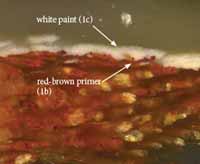

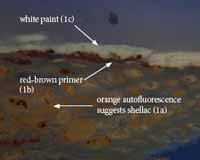

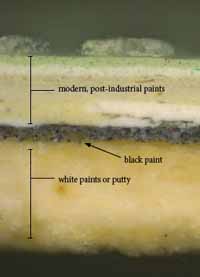

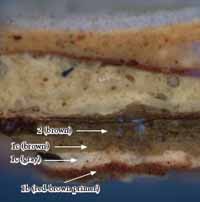

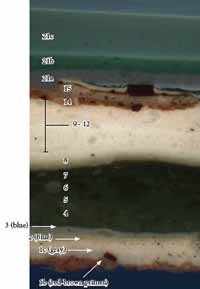

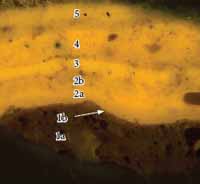

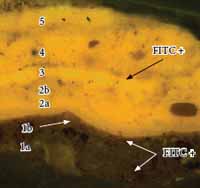

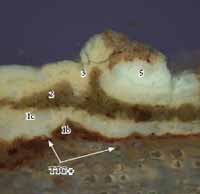

In the first generation (Brush c. 1719), the stair passage woodwork was painted with a rich, glossy warm brown color. This finish was built up in five layers— a shellac sealant (1a), a thin red-brown primer (1b), a coarsely ground gray paint (1c), a brown paint (1d), and a plant-resin varnish (1e). This finish was found on most woodwork in the stair passage (with the exception of the door leafs to the parlor and dining room, and some 19th-century replacement balusters on the stair), suggesting that all elements are contemporary. The rest of the first-floor rooms appear to have been painted gray, using the same shellac sealant (1a), thin red-brown primer (1b), and two coats of the same gray paint (1c, 1d) used in the stair passage. This gray finish was also found in the upper-floor southwest chamber. In the upper floor northwest chamber, the woodwork was primed with red-brown and painted white. In the parlor, remnants of the gray finish were found on the architrave casing of the doorway leading into the passage, and the door leaf of the doorway leading from the parlor to the rear chamber. It was not found anywhere else in the parlor, suggesting that these elements may be all that remain of the Brush-era woodwork in this room. In the northeast (rear) chamber, the first-period gray was found on both the door leaf and architrave leading to the parlor. This strongly suggests this door leaf is in its original orientation and location. There was no evidence of Brush-era paint in the dining room, suggesting all of this woodwork is later.1

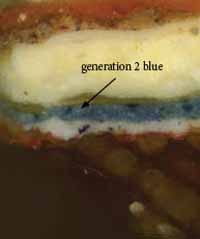

In the second generation, the first-floor northern rooms were repainted. The parlor was painted a blue-green color, and the adjoining rear chamber was painted a olive green color and coated with an oil-based varnish. It is unclear exactly when these paints were applied, but there is a thin layer of grime on the surface of the proceeding gray paint, so it may reflect a Russell/Cary finish (c.1728-1742). The absence of first period woodwork in the dining room makes it impossible to determine its color in this phase.

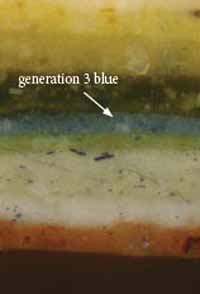

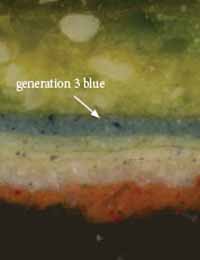

Again, in the third generation, only the first-floor northern chambers were repainted. Both the parlor and adjoining rear chamber were painted with the same coarsely-ground deep blue paint, chromatically linking these two spaces. This same deep blue paint was found upstairs in the southwest chamber. The finish in the dining room could not be determined.

In the fourth generation, the paint chronologies confirm that significant renovations occurred to the house. This period could reflect Russell/Cary (c.1728-1742), or Everard Period I (c.1756). The stair passage was re-painted for the first time, in a dark brown color. During this period, the door leafs leading from the passage to the first-floor west rooms were installed. They were primed with a red-brown primer before being painted brown to match the rest of the passage.

In the dining room, the chair rails and door and window architraves were installed and also primed red-brown and painted the same dark brown color used in the stair passage. This dark brown was also found in the upstairs northwest chamber.

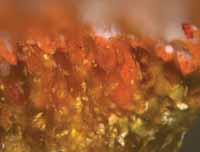

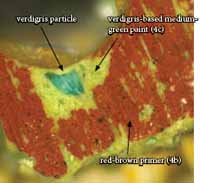

In the parlor, the cornice, chair rails, and present window and door architraves were installed, primed red 10 brown and painted with a coarsely-ground light green paint made with lead white and verdigris, a costly pigment whose tendency to oxidize necessitates frequent re-applications, which was seen in the paint history of this room.

The rear chamber adjacent to the parlor appears not to have been repainted in this period, and would have remained the same deep blue color from the previous generation.

In generation 5, the parlor verdigris green was re-applied, and the stair hall appears to have been repainted brown, in a similar hue to the previous generations. This period might represent necessary maintenance to 'spruce up' the most visible and high-status spaces in the house, since only these two rooms were painted.

Generation 6 saw major improvements to the interior of the house, which reflects Everard Period II (c.1770). In the parlor, the paint evidence confirms that the paneled wainscot, paneled chimneybreast and paneling around the doorway to the rear chamber was installed. This new, refined woodwork was coated with a white primer and painted a deep green color made with verdigris. The existing parlor woodwork was also painted with the same deep green paint to match the new additions. The adjacent rear chamber was painted with the same deep green paint, repeating the chromatic link seen between these two spaces in generation 3.

In the dining room, the paint evidence confirms that the paneled wainscot and cornice were installed (most likely the chimneybreast and overdoor on the east wall are contemporary with this period, but paint samples were not collected from these elements). All of the woodwork was painted a tan color, to incorporate the new woodwork with the old, while the door leafs were painted dark brown.

The southeast wing (present study) is believed to have been constructed in this period. The evidence is fragmentary, but suggests the woodwork was painted the same tan found in the adjacent dining room. It is unclear what color the door leafs in the study were painted (the door leaf presently installed appears to have been re-used from elsewhere in the house).

In generation 7, the dark verdigris-green paint in the parlor was re-applied, as it was most likely starting to darken and oxidize, an inherent difficulty of this copper-based pigment. This is believed to have occurred later during Everard's occupancy (c.1770-1781). It is also possible that the dining room and study were repainted (using the same colors as in the previous generation), during this time.

After Everard's occupancy, it becomes more difficult to assign particular generations to certain time periods. Some contradictions arise: for instance, the southeast study was supposedly in place c.1770s-1780s, but might have been demolished within a decade or two of its construction. But three paint generations were found on the woodwork in this space. This suggests very frequent painting for such a short-lived space, or, more likely, that this wing was in place longer than previously believed.2

Following the initial colorful interiors preferred by the earliest occupants, all spaces (with the exception of the stair passage) experienced multiple generations of white and off-white paints (in some cases, even very pale blues). These could date to the late 18th century and possibly up to the mid-19th century. After this prolonged white campaign, bolder, warmer colors made another appearance, often paired with imitation wood-graining finishes. This could reflect the mid-late 19th century treatments. After this era, the interior appears to have been painted infrequently up to the restoration. One campaign of dark brown/mauve found throughout the house may reflect the aesthetics of the late-19th century- early 20th century. Following this, some of the spaces, notably the stair passage and dining room, were painted a bright white with an industrially prepared, 20th-century paint. This is the color that appears to have been in place when the house was re-painted during the restoration, in 1949.

11 Table 1. EVERARD HOUSE: Early interior decorative history*

Table 1. EVERARD HOUSE: Early interior decorative history*

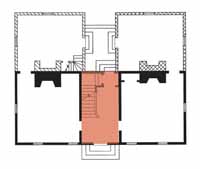

STAIR PASSAGE (first and upper floors)

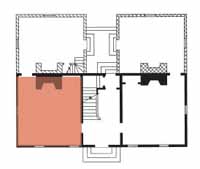

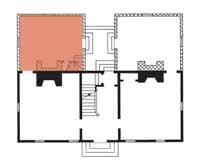

Above: First-floor plan, stair passage highlighted in red.

Above: First-floor plan, stair passage highlighted in red.

Description:

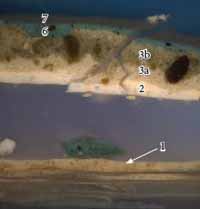

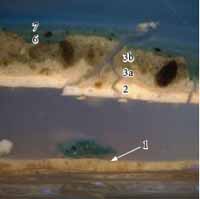

The stair is an open-type with treads ornamented with wood brackets carved in an ornate floral/scoll design. The walls feature paneled dados with surbases and crosseted door architraves. Dendrochronology carried out in 2006 determined that the wood for the stair framing and treads was cut in early 1719 (Klee 2011, 6), which would suggest that the staircase and passage woodwork were installed by John Brush.

On-site, CWF architectural historians Edward Chappell and Jeff Klee observed strong discrepancies in the construction of the stair, in particular amongst the balusters, which suggested that certain stair elements could post-date the rest of the stair. (It was hoped that the paint evidence would throw light on this theory).

There was no indication of plaster or an earlier wall surface behind the present stair and wainscot, suggesting that the present finishes are the first and only decorative treatment (Klee 2011, 12).

Summary of Welsh (1991) paint findings:

Welsh concluded that all stair passage woodwork had "identical layering sequences, suggesting that all features are early and original"(Welsh 1991, 7). The first three generations are listed in the table below. The remaining generations were described as a series of browns, olives, and whites.

| Generation | Description | Suggested date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | light brown + dirt | Everard, late 1700s | exposed for long period of time |

| 2 | light gray oil paint + dirt (black baseboards and stair skirting) | Everard (1756) | exposed for 15-25 years |

| 1 | medium red-brown oil paint + dirt | Brush (1719) | exposed for long period of time |

Summary of present (2012) paint findings:

For a condensed presentation of all stair passage results, see table 2 (page 15).

Approximately sixteen decorative generations were identified in the stair passage. The absence of dirt on the surface of the wood indicates that the stair passage was painted soon after its construction. The same first period finish was found in all samples, which suggests that all of the stair passage woodwork is contemporary, or was at least painted in the same period.

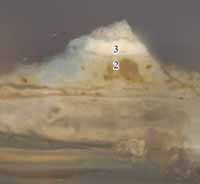

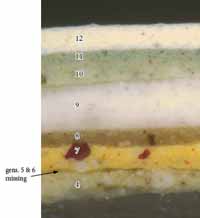

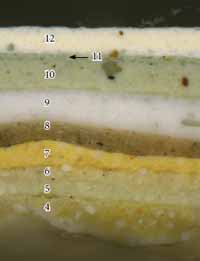

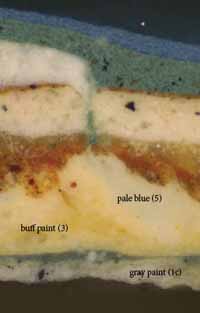

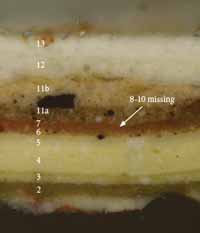

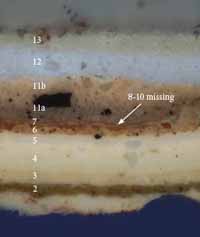

The interpretation of early finishes was very different from Welsh's 1991 study, the biggest difference being the assignment of the first generation red-brown as a primer, rather than a finish coat. This was determined via high magnification microscopy (400x), which determined that there was no dirt on the surface of the red-brown paint, and in fact very few "hard boundaries" to suggest that this paint had dried completely before the gray paint was applied. The same condition was observed for the second generation gray paint, suggesting that it was not a finish coat, but an intermediate paint layer in the first finish generation, which appears to have been a glossy brown finish. The first five generations are summarized in the following table:

| Generation | Layer | Description | Suggested date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 5b | varnish | ||

| 5a | red-brown paint | |||

| 4 | 4b | varnish | ||

| 4a | red-brown paint | |||

| 3 | 3b | varnish | Everard (1770s)? | Everard makes major renovations to interior first floor rooms but unclear which paint generation in stair passage is attributed to him |

| 3a | dark brown paint | " | " | |

| 2 | 2 | dark brown paint | Russell/Cary (1728-1742) or Everard Period I (1756)? | first finish on door leafs to west rooms, and contemporary with chair rails and architraves in parlor and dining room |

| 2a | red-brown primer | " | " | |

| 1 | 1e | varnish | Brush (1719) | all boundaries between layers are very amorphous, as if applied when still fresh. No dirt observed between layers |

| 1d | warm brown paint | " | " | |

| 1c | gray paint | " | " | |

| 1b | red-brown primer | " | " | |

| 1a | shellac | " | " |

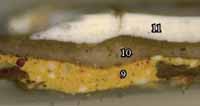

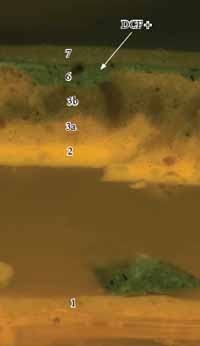

The first generation is comprised of five layers: a shellac sealant (1a), followed by a thin layer of deep red-brown primer (1b), a coarsely ground gray base coat (1c), a warm brown paint (1d), and a clear varnish (1e). This stratigraphy was found on almost all passage woodwork, including the staircase, the arched header over the door to the rear passage, the wainscot, the first-floor door architraves, and second-floor door leafs. The second-floor door architraves were stripped and contained mostly modern paints, but remnants of the first-generation red-brown primer was seen deep in the wood cells, so these architraves appear to be first-period.

The second generation is a thick layer of coarsely-ground dark brown paint which contains mostly brown and golden-yellow pigment particles, with occasional white and black particles. This generation was usually observed to have a disrupted, uneven surface suggesting it was exposed for a long period of time. On the first-floor door leaves to the parlor and dining room, this brown generation was the first to have been applied, on top of a red-brown primer (2a), suggesting these leafs were later additions.

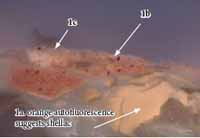

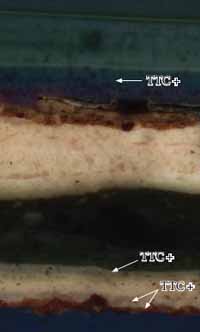

14This red-brown primer on the door leafs is not the same as the first generation red-brown primer in the rest of the stair passage, but appears to be contemporary with generation 4 in the first-floor northwest parlor. This was determined via repeated visual examination at high magnification (400x), which revealed that the first generation red-brown primer in the passage was slightly lighter in color and had a brighter autofluorescence than the later red-brown, which was darker and had little autofluorescence in UV light.

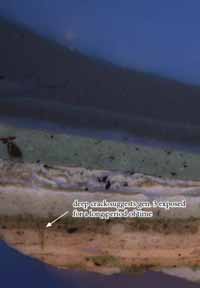

Generation 3 is another dark brown paint (3a), similar in color to the previous generation, although more thinly applied. It was coated with a thin layer of varnish (3b). This might date to the second Everard period (1770s). Generations 4 and 5 are coarsely-ground red-brown paints and clear varnishes. It is not clear when these finishes were applied, as the passage appears to have been painted independently of the rest of the house (with the exception of the first period).

As directed by E. Chappell, samples were taken from some balusters that appeared to be of a different style than the majority of balusters on the stair. The results confirmed that these balusters were later in date (see pp. 32-35). The earliest coating was a coarsely-ground pinkish-red paint that aligns with generation 7 in the rest of the passage, suggesting that these balusters were added much later, possibly the mid-19th century. The dutchmen patches on the bases of some balusters were sampled and found to contain only modern, 20th century paints. This would suggest that these repairs were made by CWF.

The paint history of the door leaf to the cellar does not align with any of the passage woodwork, or any other stratigraphies identified in the house to date. It is possible that this leaf was re—used from another house. The sample from the trim surrounding the cellar entrance was incomplete but the extant paints suggest that the trim is contemporary with the rest of the woodwork in the passage.

Table 2. EVERARD STAIR PASSAGE: decorative history (continued on next page)

Table 2. EVERARD STAIR PASSAGE: decorative history (continued on next page)

Table 2. EVERARD STAIR PASSAGE: decorative history (continued from previous page)

Table 2. EVERARD STAIR PASSAGE: decorative history (continued from previous page)

The cellar door leaf was not included in this chart because the sample was fragmentary and difficult to interpret. There was enough evidence to show that its early finishes do not align with the stair passage, suggesting it might have been re-used from another house.

STAIR PASSAGE — SAMPLE LOCATIONS

staircase, first floor, south partition

staircase, first floor, south partition

stair rise paneling, first floor

stair rise paneling, first floor

upper floor, entrance to SW room

upper floor, entrance to SW room

upper floor, entrance to NW room

upper floor, entrance to NW room

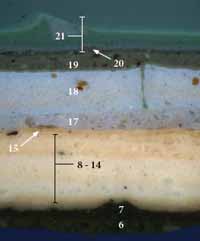

first-floor, stair rise (EV 17 taken from patch, EV 18 taken above patch)

first-floor, stair rise (EV 17 taken from patch, EV 18 taken above patch)

first-floor, stair rise (EV 19 taken area above patch, EV 20 from patch)

first-floor, stair rise (EV 19 taken area above patch, EV 20 from patch)

first-floor, stair rise, baluster 22 from bottom (EV 22 taken area above patch, EV 21 from patch). Appears to be Period I

first-floor, stair rise, baluster 22 from bottom (EV 22 taken area above patch, EV 21 from patch). Appears to be Period I

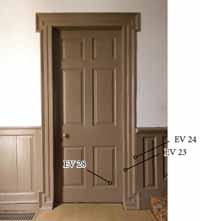

first-floor, entrance to NW parlor (photo J. Klee 2011)

first-floor, entrance to NW parlor (photo J. Klee 2011)

first-floor, entrance to SW (dining) room

first-floor, entrance to SW (dining) room

first-floor, door leaf to SW (dining) room

first-floor, door leaf to SW (dining) room

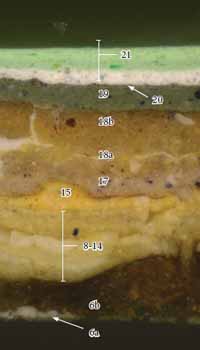

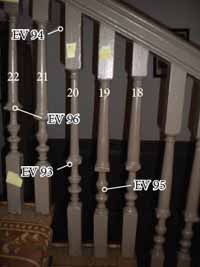

balusters 18-20 (from right to left). Baluster 20 is believed to be first-period, while balusters 18 & 19 are possibly later additions (EAC, personal comment, Dec. 2011).

balusters 18-20 (from right to left). Baluster 20 is believed to be first-period, while balusters 18 & 19 are possibly later additions (EAC, personal comment, Dec. 2011).

baluster 5 (up from bottom). This appears to be of the later style (EAC, personal comment, Dec. 2011).

baluster 5 (up from bottom). This appears to be of the later style (EAC, personal comment, Dec. 2011).

upper floor, door leaf from passage to SW chamber

upper floor, door leaf from passage to SW chamber

upper floor, door leaf from passage to NW chamber

upper floor, door leaf from passage to NW chamber

First floor, lobby beside door to cellar stair, south wall

First floor, lobby beside door to cellar stair, south wall

First floor, lobby beside door to cellar stair

First floor, lobby beside door to cellar stair

STAIRCASE - NEWEL POST

Sample EV 13: newel post on upper floor, south side, 22" up from floor

Sample EV 13 contained a very clear example of the first and second finish generations. The "soft" boundaries between the five layers that make up the generation 1 suggest they were all applied within a relatively short period of time. The disruption of the second generation brown paint suggests it was exposed for a long period of time, possibly Everard period I (1756).

STAIRCASE — DECORATIVE BRACKET

Sample EV 1: decorative bracket under 6th stair up from bottom, underside

Sample EV 1 suggests that the early finish history of the decorative brackets aligns with the rest of the stair passage woodwork, suggesting all surfaces were painted at the same time, with the same paint/color. Since there is no dirt on the surface of the wood, this paint would have been applied shortly after the stair was constructed by John Brush c.1719.

STAIRCASE — HANDRAIL

Sample EV 5: handrail fascia between first and second landing, just under cap

Sample EV 5 suggests that the early finish history of the handrails align with the rest of the stair passage woodwork, suggesting all surfaces were painted at the same time with the same paint/color. This paint would have been applied shortly after the stair was constructed by John Brush c.1719.

STAIRCASE — HANDRAIL

Sample EV 14: upper floor, handrail on stair rise adjacent to top newel

Like sample EV 5 (previous page), sample EV 14 suggests that the early finish history of the handrails align with the rest of the stair passage woodwork, suggesting all surfaces were painted at the same time with the same paint/color. This paint would have been applied shortly after the stair was constructed by John Brush c.1719.

STAIRCASE — BOTTOM RAIL ON UPPER FLOOR LANDING

Sample EV 7: upper floor, bottom rail, 6" our from newel post

Sample EV 7 was collected at the request of Edward Chappell to determine if the bottom rail on the upper floor was an addition to the stair, post—dating early baluster mortises in the floor. The paint evidence suggests that this rail is first-period and contemporary with the rest of the stair. Although some of the early paints are disrupted, the finish history (in particular generation 1), aligns with the rest of the stair passage woodwork, suggesting all surfaces were painted at the same time with the same color/paint. There is no dirt on the surface of the wood, suggesting this paint would have been applied shortly after the stair was constructed by John Brush c.1719.

STAIRCASE — BOTTOM NEWEL POST

Sample EV 92: first-floor, newel post, just under handrail

The paint evidence in sample EV 92 suggests that the newel post is first-period and contemporary with the rest of the staircase (c. 1719). It contains the same paint history as the rest of the woodwork in the stair passage, starting with the first generation red-brown primer (1b), gray base coat (1c), brown paint (1d), and varnish (1e).

STAIRCASE — HALF-BALUSTER ON NEWEL POST ON FIRST LANDING

Sample EV 3: half baluster on first landing newel, west face, plinth, 3" up from bottom

The newel post on the first stair landing was believed to be a later addition (E. Chappell, pers. comm., Dec. 2011). However, sample EV 3, taken from the half-baluster on this newel post, indicates that it contains the same first generation seen on the rest of the stair passage woodwork, which would suggest that it dates to Period I (c. 1719).2

STAIRCASE — BALUSTERS (PERIOD I STYLE)

Sample EV 91: 22nd baluster from bottom, taken from capital (just under handrail)

Sample EV 91 was taken from the 22nd baluster from the bottom, believed to be Period I (E. Chappell, pers. comm., Dec. 2011). Although the later stratigraphy is disrupted and some intermediate generations are missing, the first generation paint is relatively intact. The paint evidence suggests that this baluster does contain the first generation red-brown primer (1b), gray base coat (1c), brown paint (1d), and thin varnish (1e), which would indicate that the 22nd baluster is Period I, ie: contemporary with all other stair passage woodwork, c. 1719.

STAIRCASE — BALUSTERS (PERIOD II STYLE)

Sample EV 95: 19th baluster up from the bottom, "urn" shaped element on lower turning

Sample EV 95 was taken from a baluster that was believed to be a later installation (E. Chappell, pers. comm., Dec. 2011). The first generation applied to the wood substrate aligns with generation 7 on the rest of the stair passage. This would suggest that this baluster is a much later addition, and could possibly date to the 19th century.

This finding was confirmed by the paint chronology on suspected Period II balusters in samples EV 18 and EV 19, although the paint evidence in those samples was much less intact (see following pages).

STAIRCASE — PATCHED BALUSTERS

5th baluster up from bottom (Period II)

EV 17: taken from bottom patch on plinth

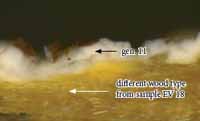

At the request of E. Chappell, some of the dutchmen patches on the balusters were sampled to understand when these repairs were made relative to the overall history of the stair. Sample EV 18 (below) was taken from a baluster, while sample EV 17 (above) was taken from a patch on that same baluster. Sample EV 17 suggests that the wood from this patch is newer and of a different type from the rest of the baluster, while the first generation white paint applied to the patch is modern, 20th-century paint which aligns with generation 11 in the passage. This evidence suggests that the patch was most likely applied by CWF.

EV 18: 5th baluster up from bottom (Period II), taken above patch

The baluster from which sample EV 18 was taken had the physical characteristics of the later balusters (In-situ examination by the author, confirmed by E. Chappell, Dec. 2011). The earliest paint on this baluster aligns with generation 7, a coarsely ground pinkish-red paint. This confirms that this baluster was a later addition to the stair passage.

STAIRCASE — PATCHED BALUSTERS

11th baluster up from the bottom (Period II)

EV 20: taken from bottom patch on plinth

As in sample EV 17 (see previous page), the wood from the patch on the bottom of this baluster appears new, and the first generation white paint applied to the patch is modern, 20th-century paint that aligns with generation 11 in the stair passage. This suggests that this patch was applied by CWF.

EV 19: 11th baluster from bottom (Period II), taken from plinth, 4" above patch

As seen in sample EV 18 (previous page), the first generation on this baluster appears to align with the 7th paint generation, a coarsely-ground pinkish-red paint. The remnant of deep red above is followed by a deep yellow paint. These are fragments of generations 8 and 9. The rest of the sample contained modern paints only. This evidence would suggest that this baluster was installed in the 7th generation, which most likely dates to the 19th century.

STAIRCASE — PATCHED BALUSTERS

22nd baluster up from bottom

EV 21: taken from bottom patch on plinth

As with the previous samples from the patched balusters, the wood from the patch in sample EV 21 appears new, and the first generation white paint applied to the patch is a modern, 20th-century paint that aligns with generation 11 in the rest of the stair passage. This patch was most likely applied by CWF.

STAIR PASSAGE — WAINSCOT PANELING

Sample EV 4: wainscot panelling directly below 7th stair

This is the most complete wainscot sample, although part of generation 1 and generations 2-3 are missing. They were most likely lost during sampling. However, the extant evidence suggests that the wainscot paneling is contemporary with the rest of the stair passage woodwork (c.1719).

STAIR PASSAGE — HEADER OVER PASSAGE DOOR

Sample EV16: arched header over passage door under stairs to east

Sample EV 16 suggests that the early finish history of the arched header over the door to the east passage aligns with the rest of the stair passage woodwork, indicating that all surfaces were painted at the same time. This paint would have been applied shortly after the stair was constructed by John Brush c.1719.

STAIR PASSAGE — DOOR ARCHITRAVES (FIRST FLOOR)

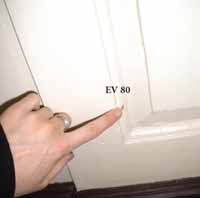

Sample EV 27: southwest room entrance door architrave, right jamb, back edge of backband

Sample EV 27 suggests that the early finish history of the crosseted architrave of the door to the southwest (dining) room aligns with the rest of the stair passage woodwork, indicating that all surfaces were painted at the same time. This paint would have been applied shortly after the stair was constructed by John Brush c.1719. Most of this architrave appeared to have been stripped, as on—site examination found paint accumulations at the back edges of the backbands only.

Sample EV 23: northwest room entrance door architrave, right jamb, inner fascia

Sample EV 23 suggests that the early finish history of the crosseted architrave of the door to the northwest room (parlor) aligns with the rest of the stair passage woodwork, indicating that all surfaces were painted at the same time. This paint would have been applied shortly after the stair was constructed by John Brush c.1719.

STAIR PASSAGE — DOOR LEAFS (FIRST FLOOR)

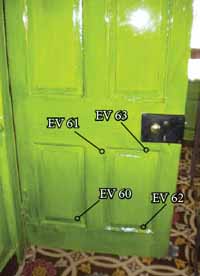

EV 28: bottom right panel of door leaf to NW room (parlor)

The complete stratigraphy for the door leaf to the northwest room (parlor) is shown above. See next page for detail of early layers.

In later generations, the door leaves were not always painted the same as the rest of the stair passage woodwork, which made the alignment of particular generations difficult.

Comparison of this sample to the rest of the stair passage woodwork suggests that this leaf was installed in the second period, when the woodwork was painted a dark brown color (2b). However, the door leaf was first primed with a red-brown primer (2a), before it was painted with the brown.

The installation of this leaf in the second period was also confirmed by the parlor-side stratigraphy (see sample EV 63, page 59).

EV 28: bottom right panel of door leaf to NW room

DETAIL OF EARLIEST PAINTS

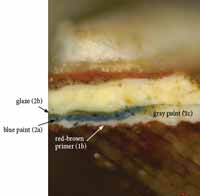

The earliest paint stratigraphy in sample EV 28 is shown above. The first generation is a red-brown primer. This is not the same as the red-brown primer found in the rest of the stair passage, but appears to have been applied in the second generation as a preparatory layer for the dark brown paint that was found in the rest of this space. This suggests that this leaf was installed a generation later than the rest of the stair passage woodwork, which was confirmed by the paint stratigraphy on the parlor-side of this leaf.

EV 29: bottom right panel of door leaf to SW room

The early paints in sample EV 29 from the door leaf to the first-floor SW (dining) room are very disrupted, but the earliest finish applied appears similar to that found on the NW parlor door leaf, ie: a red-brown primer (2a) and dark brown paint (2b) that aligns with the second generation finish in the rest of the stair passage.

This evidence suggests that both door leafs for the western first-floor room were installed in the second generation.

STAIR PASSAGE — CELLAR DOOR LEAF

EV 30: lower right raised panel

The paint history of the cellar door is different from the rest of the woodwork in the stair passage, suggesting it was moved here from another location in the house.

STAIR PASSAGE — CELLAR DOOR TRIM

EV 31: trim at left side of door

This sample is missing wood substrate so it could not be determined if the first generation finish was present, but the evidence suggests the cellar trim is contemporary with the rest of the woodwork in the passage.

STAIR PASSAGE — DOOR ARCHITRAVES (UPPER FLOOR)

Sample EV 10: entrance to SW room from stair passage, inner fascia

The evidence in sample EV 10 suggests that this upper-floor door architrave was stripped. Most of the extant finishes are twentieth-century coatings consisting of finely-ground red-brown paints with a dim autofluorescence (indicative of a synthetic binding media), most of which are coated with alkyd-based varnishes (blue autofluorescence in UV). However, remnants of the first paint generation still survive in the wood cells, which would suggest that this architraves is contemporary with the rest of the stair passage woodwork.

STAIR PASSAGE, Upper floor — Door Architrave to NW chamber

Sample EV 11: entrance to NW room from stair passage, backband

The evidence in sample EV 11 suggests that this second-floor door architrave was also stripped. Like sample EV 10, most of the extant finishes are twentieth-century coatings consisting of finely-ground red-brown paints with a dim autofluorescence (indicative of a synthetic binding media), most of which are coated with alkyd-based varnishes (blue autofluorescence in UV). However, remnants of the first paint generation still survive in the wood cells. Although this evidence is very disrupted, it would suggest that this architrave is contemporary with the rest of the stair passage woodwork.

Sample EV 110: architrave to passage, stop of east jamb

Jeff Klee requested that this sample be taken from the stop of the doorway to the northwest chamber on the upper floor. The surface appeared to have been stripped, but there are remnants of the first generation red-brown primer and gray paint as found in the rest of the passage, suggesting this architrave stop dates to the first period. The rest of the paints appear to be modern, synthetic coatings.

STAIR PASSAGE, UPPER FLOOR — DOOR LEAF TO SW CHAMBER

Sample EV 102: upper floor, door leaf to southwest chamber, underside of bottom right panel

Although some of the early chronology is disrupted or missing, the first—generation paint evidence on the door leaf to the upper-floor southwest chamber aligns with the rest of the stair passage woodwork, suggesting that this leaf is original, c.1719.

There is more of a defined boundary on the surface of the red-brown primer (1b), as compared to the rest of the stair passage samples, and there also appears to be some varnish present. It is possible that the primer on this door leaf was allowed to dry more thoroughly, and was exposed longer, before it was painted with the gray paint (1c), or that this leaf was painted red-brown and varnished on its own, separate from the rest of the stair passage woodwork. The reason for this anomaly is not immediately clear. See next page for further discussion.

STAIR PASSAGE, UPPER FLOOR — DOOR LEAF TO NW CHAMBER

Sample EV 104: upper floor, door leaf to northwest chamber, right stile

Only the earliest paints from sample EV 104 are shown above. The paint evidence aligns with the first generation in the rest of the stair passage, consisting of a shellac sealant (1a), a red-brown primer (1b), a gray base coat (1c), a brown paint (1d), and a thin varnish layer (1e, not seen here).

As seen on the other upper-floor door leaf (previous page), there is more of a defined boundary on the surface of the red-brown primer (1b), as compared to the rest of the stair passage samples, and there also appears to be some varnish present. It is possible that the primer on this door leaf was allowed to dry more thoroughly, and was exposed longer, before it was painted with the gray paint (1c), or that this leaf was painted red-brown and varnished on its own, separate from the rest of the stair passage woodwork. The reason for this anomaly is not immediately clear. However physical evidence such as the archaic quality of the ovolos, the arrangement of the panels (with a thin lock rail), and particularly the foliated hinges strongly suggest that this door leaf is first period (Klee, personal comment, May 24, 2012).

STAIR PASSAGE, FIRST FLOOR — PEGBOARD IN LOBBY

Sample EV 108: first floor, left corner of pegboard in lobby beside door to cellar stair

The sample from the pegboard contains the same first generation gray paint seen in the rest of the stair hall, suggesting this element dates to the Brush-era (1719). The red paint on the bottom of the sample is not the Brush-era red-brown primer but rather one of the later red-brown paints that have flowed under the disrupted early paints.

STAIR PASSAGE, FIRST FLOOR — PANELING IN REAR LOBBY

Sample EV 109: first floor, beaded rear facing of paneling in stair passage rear lobby

The beaded paneling in the stair passage lobby contains the same first generation red-brown primer, gray paint, and brown finish seen in the rest of the stair passage, suggesting this element dates to the Brush era (1719). The rest of the early paints are very disrupted.

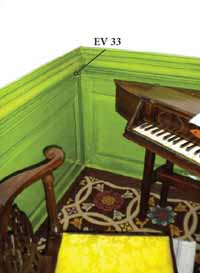

FIRST-FLOOR, NORTHWEST PARLOR

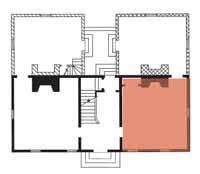

First-floor plan, northwest parlor highlighted in red.

First-floor plan, northwest parlor highlighted in red.

Description/History:

Physical examination suggests that when John Brush constructed the house, the first-floor northwest parlor had only baseboards and door and window trim, with the walls plastered to the ceiling and whitewashed (Klee 2011, 12). The cornice and chairboards were added later, most likely during the occupation of Elizabeth Russell and Henry Cary (1728-1742), or Everard's early occupancy (1756) (Klee 2011, 18). The paneling, wainscot, and mantel were all installed when Thomas Everard completed an extensive remodeling of the house c.1770-1773 (Klee 2011, 20). At that time, the present Georgian-style window and door architraves replaced most of the existing Brush-era trim (J. Klee, personal comment, Dec. 2011).

Summary of Welsh (1991) paint study findings:

Welsh concluded that the first generation in the parlor was the medium red-brown paint found throughout the house. He found a layer of dirt on the surface of this paint that suggested it was a finish coat as opposed to a primer. Generation 2 was a medium-green paint made with lead white and verdigris, followed by a glaze with a small amount of verdigris. This generation was also covered with a layer of dirt. In the third generation the woodwork was painted a deep green finish made with the medium-green base coat and two layers of deep verdigris green glaze. Generation 3 was the earliest finish on the wainscot, chimneybreast paneling, and mantel, which were known to have been installed by Thomas Everard c. 1770.

| Generation | Description | Suggested date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | medium green verdigris paint + two coats dark green verdigris glaze | Everard, late 1700s | first generation on wainscot, chimneybreast paneling and mantel |

| 2 | medium green verdigris paint + thin verdigris glaze + dirt | Everard (1756) | |

| 1 | medium red-brown oil paint + dirt | Brush (1719) | exposed for long period of time |

Summary of present (2012) paint study findings:

For a presentation of all parlor results, see table 3 (page 54).

The 2011 findings were very different from Welsh's interpretation and have resulted in a re-evaluation of the physical history of the parlor.

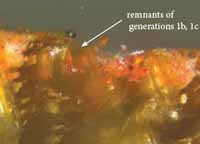

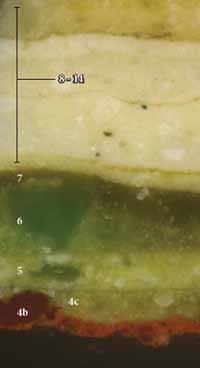

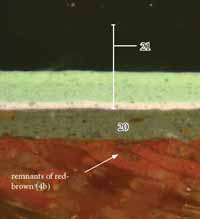

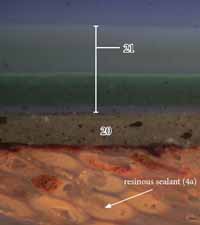

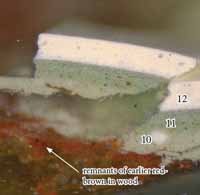

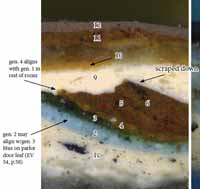

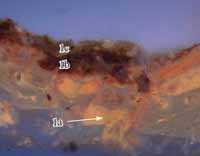

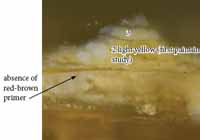

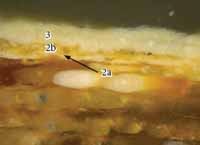

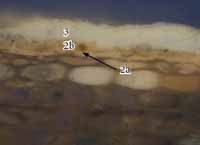

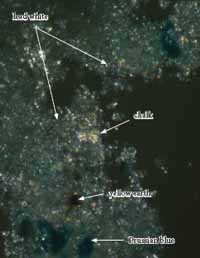

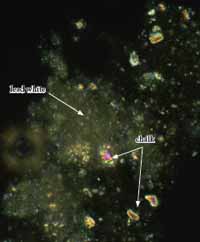

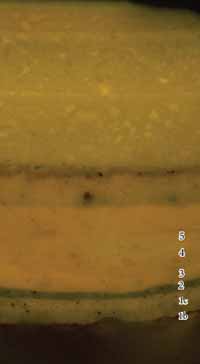

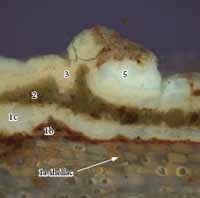

The present investigation found that the door leaf to the rear (NE) chamber and the jamb liner on the parlor side of the door casing to the passage contained three early finish generations that pre-date anything else in the parlor (Welsh only found this early stratigraphy on the door leaf to the rear (NE) room. He appears to have concluded that this leaf was not original to the space, and does not discuss it in his report). In these samples, the earliest finish generation is a resinous sealant (1a), followed by a thin layer of coarsely ground red-brown primer (1b), and a gray paint made with lead white and large, coarsely-ground particles of charcoal (1c). This is the same as the first generation paint in the stair passage, and is interpreted here as a Brush-era finish. Generation 2 is a blue-green paint, and generation 3 is a deep blue paint.

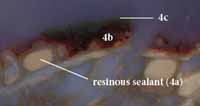

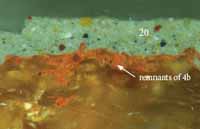

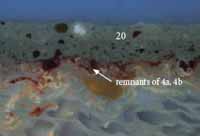

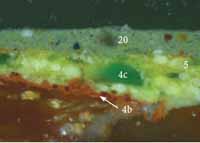

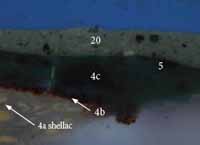

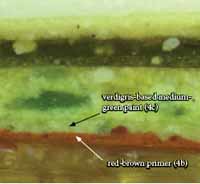

The comparative evidence determined that in generation 4, the chair rails, cornice, door leaf to passage, and present door and window architraves were installed and painted the same light verdigris green. The earliest generation on these new elements was a shellac sealant (4a), red-brown primer (4b), and the light green paint. (4c) (Welsh identified this light green as generation 2, because he considered the red-brown primer (4b) to be a finish coat). Although most of the chair rails and architraves were stripped, remnants of the red-brown primer in the wood suggests these elements are contemporary. Generation 4 could represent the Russell/Cary-era (1728-142), or Everard Period I (c.1756). The light green verdigris paint was re-applied in generation 5.

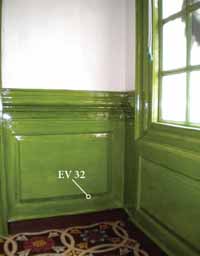

The comparative evidence suggests that in generation 6, the chimneybreast paneling and wainscot were installed, and all parlor woodwork was painted a deep-green color made with verdigris. CWF architectural historians have associated the paneling with Thomas Everard's extensive renovations c.1770, so generation 6 has been interpreted as Everard period II. This deep green paint was re-applied in generation 7, most likely during a later Everard period.

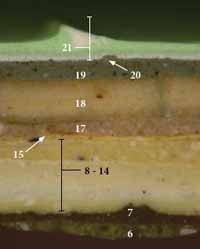

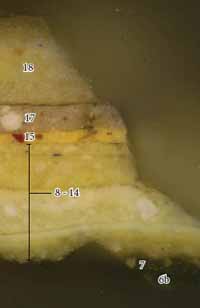

Generations 8—14 are a series of white, pale blue, and off-white paints. Generation 15 is a medium-yellow paint that contains coarsely-ground deep red particles, suggesting it was prepared by hand, and could be a mid-19th-century paint. The comparative evidence indicates that in this finish generation, all woodwork was painted with this medium-yellow paint, and the door leaves were faux-wood grained, using the medium-yellow as a base coat for graining. There is a layer of grime on the surface of this paint which suggests it was exposed for a long period of time. In generation 16, the door leaves were painted black but the rest of the woodwork was not newly painted.

In generation 17, the room was painted in a polychrome scheme, with grayish-brown paneling and door leafs, and deep mauve trim. The parlor was again painted in a polychrome scheme in generation 18, with medium-brown paneling and door leafs, and tan-colored trim. These are most likely late 19th-century or early 20th-century color schemes.3

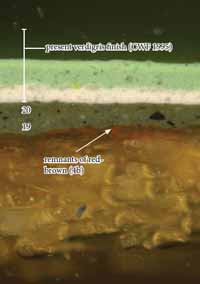

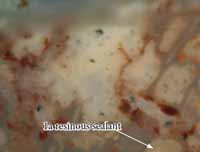

Generation 19 was painted by CWF in 1949 and consists of red-brown door leafs and gray-green woodwork. This was repeated in generation 20. Generation 21 is a replication of the 18th-century verdigris green color scheme. It was applied in 1995 in response to Welsh's findings and consists of a white primer, a bright blue-green base coat and a bright green glaze made with verdigris in colophony resin (C. Swan, personal comment, Dec. 2011).

Table 3. EVERARD HOUSE, First-floor NORTHWEST PARLOR: Complete decorative history

Table 3. EVERARD HOUSE, First-floor NORTHWEST PARLOR: Complete decorative history

Note: — findings suggest that door leaf to passage is later (this is consistent with passage-side evidence on same leaf)

— leaf to rear chamber (NE room) and door casing to passage is first-period (aligns with gen. 1 (1719) on stair passage woodwork)

Door Leafs and Architraves

Summary of results:

The samples taken from the parlor door leafs and door architraves presented some interesting and complex comparisons. The casing of the doorway to the stair passage (EV 58), and the door leaf to the northeast (rear) chamber (EV 54), contained paints that pre-dated any finishes in the parlor (p. 57).

On the south wall doorway (leading to the passage), on-site visual examination suggested that the Georgian-style architrave moldings were later 18th-century additions that replaced the Brush-era trim (J. Klee, pers. comm., Dec. 2011). Unfortunately, the cross-section evidence suggests that the moldings were stripped (EV 64, p..60), so it was not possible to assign a relative date for their installation. However, the sample from the jamb liner on the passage-side of the casing contained early paints that were consistent with the generation 1 in the stair passage, indicating this casing is first-period (EV 58, p. 57, 59), because the first three paint generations on this casing pre-date anything found in the parlor. The same paint history was found on the door leaf to the rear chamber, suggesting these two elements are earlier than the rest of the parlor woodwork.

The paint history of the door casing to the stair passage and door leaf to the rear chamber begins with a shellac sealant (1a), a thin red-brown primer (1b), and a light gray paint (1c). The color, thickness, pigment particle size and dispersion strongly suggests this gray paint is the same as that found in the stair passage (1c). However, unlike the stair passage (which was then painted a dark brown (1d), with varnish (1e)), the gray paint in the parlor was the finish layer. This finish would date to the Brush-era, c.1719. This is a surprising discovery, because the complex ovolo-molded panels of this door suggest a mid-18th-century date to the architectural historians (E. Chappell, personal comment, Jan. 2012).

In the second generation (according to these two samples), the parlor was painted green-blue, and in generation 3, the parlor was painted a deeper blue. In generation 4, both of these samples contain the same coarsely-ground light green verdigris paint in the rest of the parlor.

The paint history of the door leaf to the passage and the door architrave to the rear chamber began with the fourth generation, starting with a shellac sealant (4a), thin red-brown primer (4b), and the same coarsely-ground light green verdigris paint (4c) discussed previously.

In generation 5, all parlor woodwork, including the door leafs and architraves, was re-painted with the coarsely-ground light green verdigris paint. In generation 6, when the chimneybreast paneling and wainscot were installed, and all parlor woodwork was painted a deep-green color made with verdigris pigment. Generation 6 has been interpreted as Everard period II. This deep green paint was re-applied in generation 7.

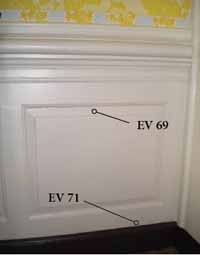

56Passage door Leaf and Architrave (parlor-side)

Sample locations

east wall, doorway to rear chamber

east wall, doorway to rear chamber

east wall, door leaf to rear chamber

east wall, door leaf to rear chamber

FIRST-FLOOR NORTHWEST ROOM (PARLOR)

Comparison of door leaf to rear chamber and door casing to passage

Door leaf to rear chamber

Door leaf to rear chamber

EV 54, UV (left) and visible (right) light, 200x

Doorway to passage — architrave casing

Doorway to passage — architrave casing

EV 58, visible (left) and UV (right) light, 200x

The samples taken from the door leaf to the rear chamber (left) and the jamb-liner of the architrave to the passage (right) contained early paints not seen elsewhere in the parlor, suggesting these elements could be the earliest in the room.

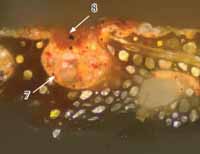

The first generation consists of a red primer (1a) and gray paint (1b). This finish was also found in the stair passage, suggesting these elements are contemporary with the woodwork in that space. Generation 2 is a blue green paint, and generation 3 is a deep blue. Generations 4 and 5 are the light verdigris-green paints seen on the chimneybreast chair rails, door architraves and door leafs in the rest of the room.

FIRST-FLOOR NORTHWEST ROOM (PARLOR)

Comparison of door leaf and architrave to rear chamber

Door leaf to rear chamber (early layers)

Door leaf to rear chamber (early layers)

EV 54, UV 9left) and visible (right) light, 400x

Door architrave to rear chamber (early layers)

Door architrave to rear chamber (early layers)

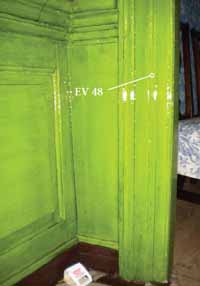

EV 48, visible (left) and UV (right) light, 400x

Comparison of the door leaf to the rear chamber (left) and its associated architrave (right) suggests that the leaf is earlier than the door architrave, which was installed in generation 4.

The early paint stratigraphy of the door architrave aligns with the door leaf to the passage and the chimneybreast chair rails. It also presumably aligns with the paint history of the other chair rails as well as the door and window architraves, which have identical profiles to this one. These elements were found to have been stripped, but remnants of red-brown primer were found in their wood cells. This would suggest that these the chair rails pre-date the wainscot but are continuous with the architraves.

Comparison of Door Leaf and Architrave Casing to Passage

Door leaf to passage

Door leaf to passage

EV 63, UV (left) and visible (right) light, 200x

Architrave casing

Architrave casing

EV 58, visible (left) and UV (right) light, 200x

Comparison of the door leaf (left) and door casing to the passage (right) suggest that the leaf was installed in generation 4. Furthermore, the door leaf aligns with the chair rails and east wall door architrave (EV 48, previous page), suggesting these elements are contemporary.

Passage door Architrave (parlor-side)

Sample EV 64: Right jamb, fascia near cyma of backband, 30" up from floor

The parlor door architrave (passage-side) was examined in detail on-site and there was no evidence of historic paints extant. This suggests that the parlor-side of the architrave was stripped at some point. There are remnants of red-brown in the wood cells, which could be from generation 4.

Chair Rails (Surbases)

Summary of results:

The cross-section evidence suggests that the chair rails on the north, south, and west walls were stripped at some recent date, as these samples contained only modern paints. However, the chair rails on the east wall paneling surrounding the doorway to the rear chamber and the chimneybreast chair rails retained complete stratigraphies from which the decorative history of the room could be postulated.

The chair rails on the chimneybreast contained more early paint generations than the chimneybreast paneling, suggesting that these chair rails were re-used from elsewhere in the room when the chimneybreast was constructed.

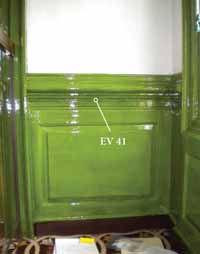

The most intact chair rail samples were taken from the chimneybreast south face (EV 38, p. 65), and the chair rail on the paneling surrounding the east doorway (EV 36, p. 66). These samples suggest that the earliest generation on the chair rails consists of a resinous sealant applied to the wood (4a), a thin layer of a coarsely-ground red-brown primer (4b), and a coarsely ground light green verdigris-based paint (4c). This was the earliest generation on the door leaf to the passage and the door architrave to the rear chamber, while remnants of the red-brown primer were also found on the window architraves and cornice. This would suggest that these elements are contemporary.

In the fifth generation, the light green verdigris paint was re-applied to the chair rails (and all other contemporary woodwork). In generation 6, the chimneybreast, wainscot, and paneling were installed and all woodwork in the room was painted a deep green color made with verdigris pigment. This paneling is believed to have been installed by Thomas Everard c.1770 when he made substantial renovations to the house, so this finish is considered Everard period II. In generation 7, the deep green verdigris-based paint was re-applied.

62 south wall, 40 ½" from east wall

south wall, 40 ½" from east wall

Chair Rails

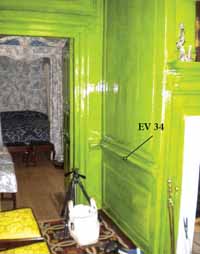

Sample EV 34: Chimneybreast, north face, 18.5" from east wall, under bolection

Sample EV 34 is missing generation 5, the second light green verdigris paint. This is believed to be an anomaly, and does not indicate that the chair rails were unpainted in this generation.

Chair Rails

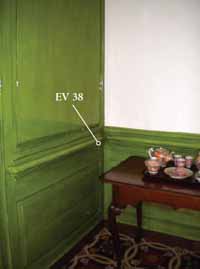

Sample EV 38: Chimneybreast, south face, 6" from east wall, under bolection

Chair Rails

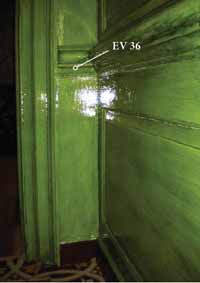

Sample EV 36: East wall, panelling around doorway to rear chamber, right side of doorway

Chair Rails

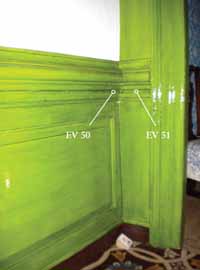

Sample EV 50: north wall, 1" out from east wall, just under bolection

Sample EV 51: east wall, 1" out from north wall, just under bolection

The cross-section evidence indicates that most of the parlor chair rails were stripped at some point, although the remnants of early red-brown paint were seen deep in the wood cells (4b). The sample taken from the east wall (EV 51) still contains some surviving early light green verdigris finishes (4c, 5), as well.

Wainscot and Paneling

Summary of results:

The comparative evidence supports the theory that the wainscot, chimneybreast paneling, and paneling around the door to the northeast (rear) chamber are all later additions to the parlor. These elements appear to post-date the chair rails.

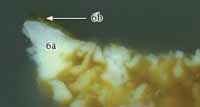

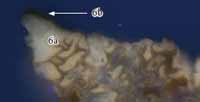

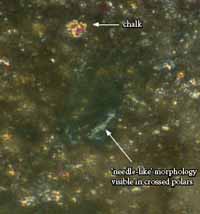

The first finish on these surfaces is a white base coat (6a) and a deep green verdigris paint (6b), which aligns with generation 6 on the earlier woodwork in the room. This deep green paint was re-applied in generation 7, although the boundary between the sixth and seventh verdigris paint is not always apparent, as these paints are so dark. It might also suggest that the seventh deep green verdigris paint was re-applied soon after the sixth generation, or that the seventh generation was only applied to 'touch up' certain surfaces.

This paneling is believed to have been installed by Thomas Everard c.1770 when he made substantial renovations to the house, so this deep-green verdigris finish is considered Everard period II. In generation 7, the deep green verdigris-based paint was re-applied, probably late in Everard's occupancy, which lasted until his death in 1781.

69 south face of chimneybreast

south face of chimneybreast

Wainscot

Sample EV 32: south wall, westernmost panel, lower right corner, beveled edge under raised panel

Over door panel, doorway to rear chamber

Sample EV 49: east wall, entry to rear chamber, over door panel, top ovolo of bottom rail

Paneling around doorway to rear chamber

Sample EV 52: east wall, panel under chair rail, left side of doorway

Chimneybreast paneling

Sample EV 40: south face, above chair rail

Chimneybreast paneling

Sample EV 35: north face, below chair rail

Window Sash and Architraves

Summary of results:

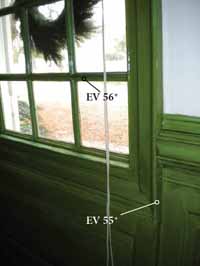

The window architraves appear to have been stripped, as only a few generations of twentieth-century paints were present. However, there were remnants of red-brown paint deep in the wood cells, most likely from generation 4. This evidence is fragmentary, but it could suggest that the window architraves were contemporary with the chair rails, door and window architraves, and door leaf to the passage.

There were no historic paints found on the window sash, so their relative dates could not be determined. However, the relatively narrow muntins suggest a late 18th-century date (E. Chappell, personal comment, Jan. 2012).

Window architrave

Sample EV 55: west wall, southern window, architrave, right jamb, back edge

Cornice

Summary of results:

All of the samples collected from the cornice (EV 65— EV 67) contained similar paint evidence. Only the most recent generations were present, suggesting the cornice was stripped just before generation 19 was applied in the mid-20th century. However, there were some remnants of red-brown paint in the wood cells, most likely from the fourth generation. This evidence was fragmentary, but suggests that the cornice is contemporary with the chair rails, the door and window architraves, and the door leaf to the passage.

FIRST-FLOOR, SOUTHWEST (DINING) ROOM

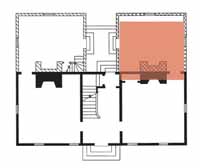

First-floor plan, southwest (dining) room highlighted in red.

First-floor plan, southwest (dining) room highlighted in red.

Description/History:

Like the first-floor northwest parlor, the physical evidence suggests that when John Brush constructed the house (c.1718), the southwest dining room had only baseboards and door and window architraves, and the walls were plastered to the ceiling and whitewashed (Klee 2011, 12). Evidence for the early wall finishes could exist on the exposed wall plate enclosed by the buffet (an Everard period I addition) on the east wall (to be sampled at a future date when all objects will be removed from buffet). The cornice and chairboards were added later, possibly during the occupation of Elizabeth Russell and Henry Cary (1728-1742) or during Thomas Everard's early occupancy (c.1756), but this is still uncertain (Klee 2011, 18).

As in the parlor, the raised—panel wainscot, mantel, and overdoor are believed to have been installed by Everard c.1770 (Klee 2011, 22). Evidence for the present wallpaper was found underneath the cornice during the restoration, and is believed to date to c.1770.

All of the plaster dates to the restoration and was not sampled.

Summary of Welsh (1991) paint study findings:

Welsh concluded that the first generation in the parlor was the medium red-brown paint found throughout the house. Generation 2 was a dark brown paint on all of the trim except for the baseboards which were painted black. The comparative paint evidence suggested that the cornice, wainscot, and mantelpiece and overdoor paneling were installed in generation 3, when the woodwork was painted a yellowish-white with dark brown baseboards and door leafs (Welsh 1991, 26).

| Generation | Description | Suggested date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | yellowish-white with dark brown baseboards and doors | Everard, late 1700s | first generation on wainscot, overdoor and mantel |

| 2 | dark brown paint with black baseboards | Everard (1756) | |

| 1 | medium red-brown oil paint + dirt | Brush (1719) | exposed for long period of time |

Summary of present (2012) paint study findings:

Many of the samples collected from the dining room were incomplete or had disrupted early paint stratigraphies, making the interpretation of this space, and its relation to the rest of the house, very difficult. In general, the findings were similar to Welsh's 1991 results, with the exception that the first-generation red-brown was identified as a primer, not a finish coat. This shifted all of the early paint generations back one generation.

The first extant generation appears to be a red-brown primer (1a) and medium-brown paint (1b). This finish was fragmentary and found only on the window architrave and the door leaf and architrave to the passage. It seems to align with generation 2 in the stair passage, suggesting it is not a Brush-era finish but could date to the Russell/Cary-era, or Thomas Everard Period I (1756). Although the evidence is fragmentary, there were remnants of the red-brown primer on the chair rails, suggesting that these were contemporary with Everard Period I.4 This color appears to have been applied to all woodwork in this room.

In the second generation, Everard Period II (c.1770), the wainscot and cornice were installed and all woodwork was painted a pale yellow, with the exception of the door leafs which were red-brown. As in the parlor, the absence of the red-brown primer on these elements suggests that they were later additions.

The sample from the window architrave contained the most intact early paint sequence, and suggests that generations 3-6 (missing from all other samples), were pale blue and off-white paints. Generation 7 is the medium-yellow paint with large red particles that was seen in the stair passage (as generation 9) and the parlor (as generation 15). In the dining room, as in those spaces, the trim was painted with the medium-yellow and the door leafs were faux-wood grained using the yellow as a base coat. Generation 8 is a brown paint that is very bright in reflected UV light. This generation appears to align with generation 10 in the stair passage and generation 17 in the parlor.

Generation 9 is a bright white paint that appears to date to the twentieth century. Generations 10 and 11 are green paints that were applied by CWF. Generation 12 is the current pale yellow paint, a replication of Everard Period II (c.1770) as identified by Frank Welsh in 1991.

Table 4: EVERARD HOUSE, First-floor SW (DINING) ROOM: complete decorative history

Table 4: EVERARD HOUSE, First-floor SW (DINING) ROOM: complete decorative history

note:

— leaf to rear study (SE room) has first-period finish (consistent with gen. 1 in stair passage,also found on leaf to rear chamber in the parlor), but since it could have been taken from elsewhere, its results are presented separately.

— absence of red-brown in wainscot suggests it is later than the chair rails and architraves, installed in generation 2 (Everard, c. 1770)

FIRST-FLOOR SOUTHWEST (DINING) ROOM— Door Architrave and Leaf to Study (SE chamber)

Like the chair rails, the results suggest that the door architrave leading to the southeast study was stripped of its early paints. Remnants of a red-brown primer were found in the wood cells, which could suggest that the architrave is contemporary with the chair rails and door and window architraves (Everard Period I, 1756).

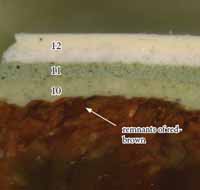

The paint evidence on the door leaf suggests it may have been moved from elsewhere in the house, as it contains generations that are first period, but pre-date anything else in the room (EV 77, p. 85).5 The first generation is the shellac sealant (1a), red-brown primer (1b), and gray paint (1c) that was also seen in the stair passage (Brush, 1719). Generation 2 is a deep blue paint that may be contemporary with the third generation paint on the door leaf to the rear chamber in the parlor (EV 54, p. 58). Generation 3 is a dark green paint not seen elsewhere in the house. In generation 4, the leaf was painted a medium-brown, which aligns with the first generation on the door leaf and architrave to the passage. In generations 5 and 6, the door was painted red-brown, after which it appears to have been scraped down, with intermediate generations missing.

Door Architrave (to Study)

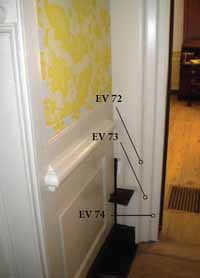

Sample EV 72: left jamb, backband

Door Architrave (to Study)

Sample EV 73: left jamb, outer fascia

Door Leaf (to Study)

Sample EV 77: bottom left panel, underside of panel at beveled edge

Sample EV 77 suggests that the door leaf to the study is original to the house. The first finish generation is the red-brown primer and gray paint found in the stair passage, suggesting these elements are contemporary (c.1719). Generation 2 is a deep blue paint that could be contemporary with generation 3 on the parlor door leaf to the rear chamber (EV 54, p. 58). Generation 3 is a deep green paint that has not been observed anywhere else in the house to this point. Generation 4 is the medium-brown paint that aligns with the first generation found on most of the dining room woodwork. Generations 5 and 6 are red-browns, after which the door appears to have been scraped down. The leaf re-aligns with the rest of the room in generation 10.

DOOR ARCHITRAVE AND LEAF TO PASSAGE

The door architrave and leaf to the passage both contain the same first paint generation, consisting of a shellac sealant (1a), a red-brown primer (1b), and medium-brown paint (1c). This was the same first generation on the door leafs in the passage (pp. 41-42), which comparison showed to belong to a later period than the stair passage woodwork, possibly Everard Period I (1756).